How to correct for aberrations in light microscopy

As aberrations eat up the signal and smear focus and image, they can give microscopists a hard time. They belong to microscopy like pathogens belong to life. We can’t do anything about the fact that they exist – but we can prevent them from spoiling our scientific images: There are ways to bring diverted rays back on track, but some are better than others, and adaptive optics with a deformable mirror beats them all.

deformable mirror or correction collar?

These are aberrations

A photon is like the Road Runner with symptoms of ADHD: Full of energy, it dashes through space with – indeed! – the speed of light, but it’s easily distracted by anything it passes on its way and will instantaneously divert from its straight path. Only that the photon’s ADHD is truly incurable: It is in the photon’s wave properties and those we cannot change. The very physics of light dictates that it is bent whenever it transits at an angle between media with different refractive indices. This phenomenon is called refraction, and the refractive index is a value for the medium’s optical density, indicating how strongly light is deflected. When refraction diverts light rays from their destined path, it smears the focus and leads to murky images. These are aberrations.

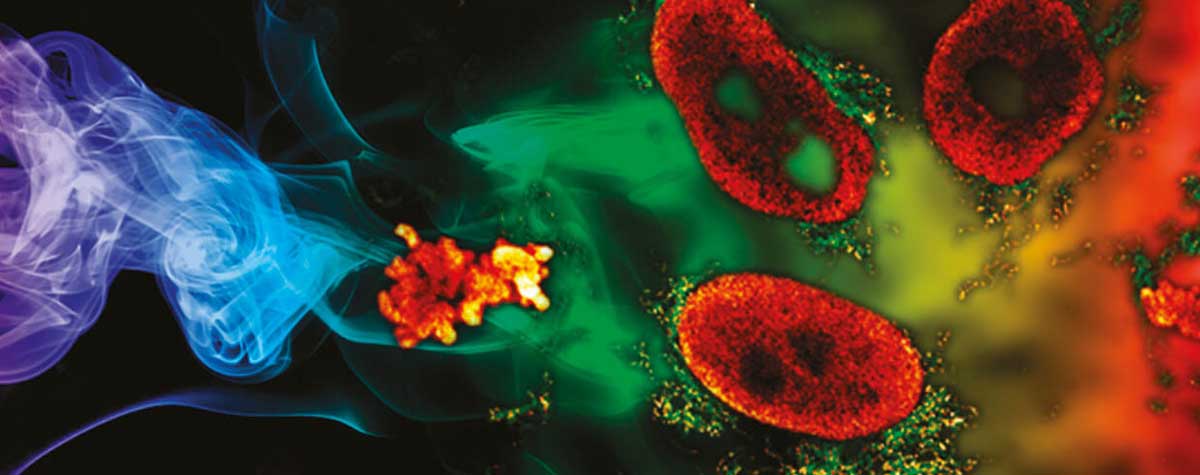

The degree by which light is diverted does not only depend on the refractive index, which usually is a function of the light’s wavelength. That’s why droplets of water in the air can split the sun’s light into its spectral parts and create a rainbow. Usually, the shorter the wavelength (and the higher the energy), the stronger the diversion.

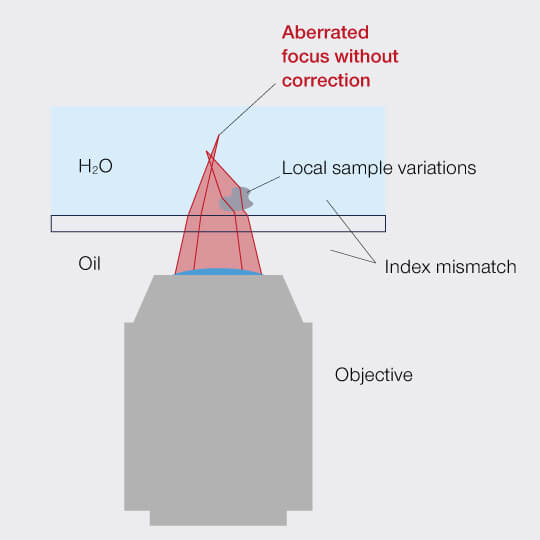

In nature we find refraction creating sights that please the eye. For a light microscopist, refraction is what makes lenses work. However, refraction can also become a nuisance. On the way from the objective lens into the sample and out again, the light has to pass air or an immersion medium, the cover slip, and the mounting medium. Even when those media are closely matched according to their refractive indices, residual unwanted refraction easily leads to aberrations.

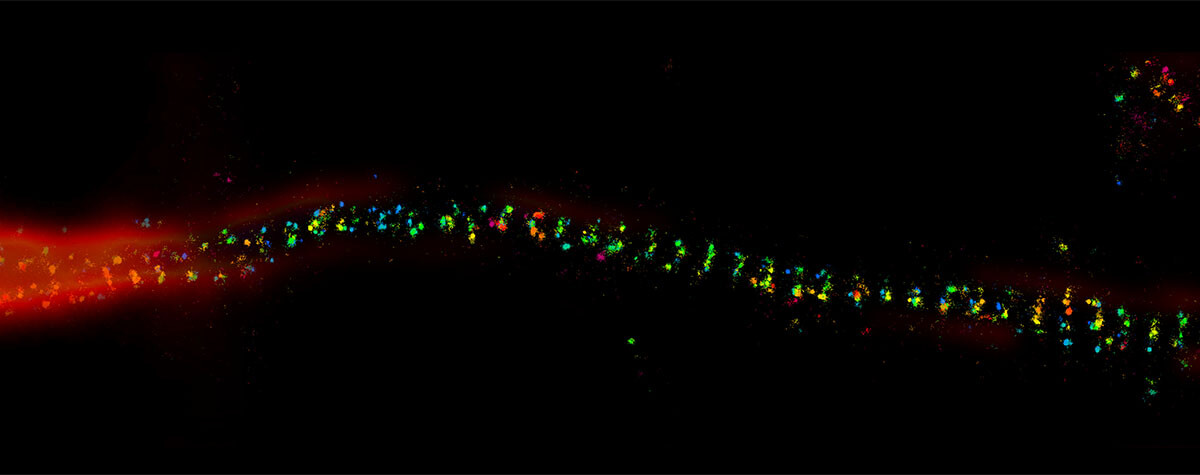

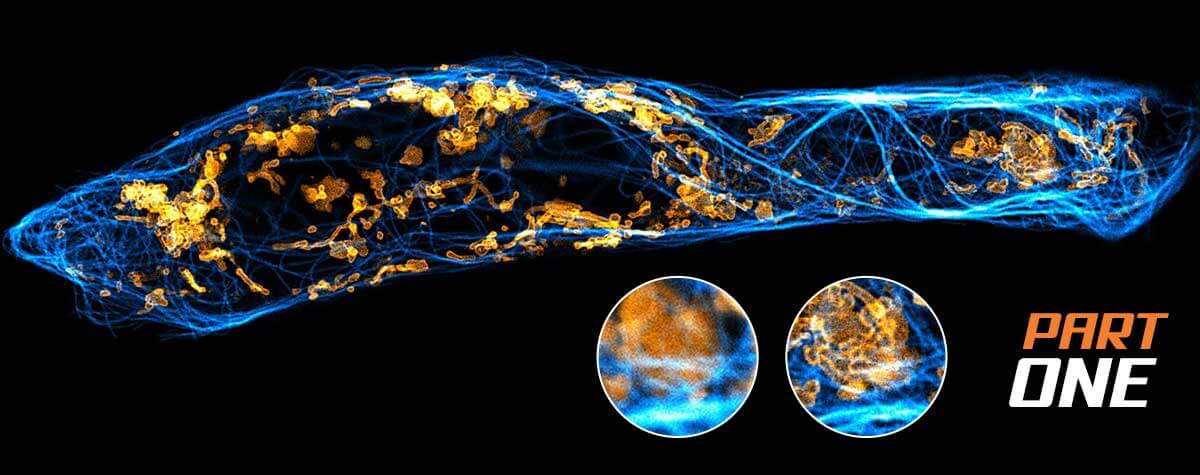

Figure 1: Aberrations distort the focus of a microscope.

Then there is the sample itself: Biological samples are chronically unordered, often inhomogeneous, and countless structures refract the light on its way. And the deeper you focus into the sample, the stronger the effect. Eventually, you will be left with hardly any signal at all.

Putting stray rays back on track

Do we have to stay at the sample’s surface then, where aberrations can at least be controlled to some degree? Do we have to accept that an image will be turbid and that valuable information hidden deeper in the sample has to remain unattainable? And that’s that?

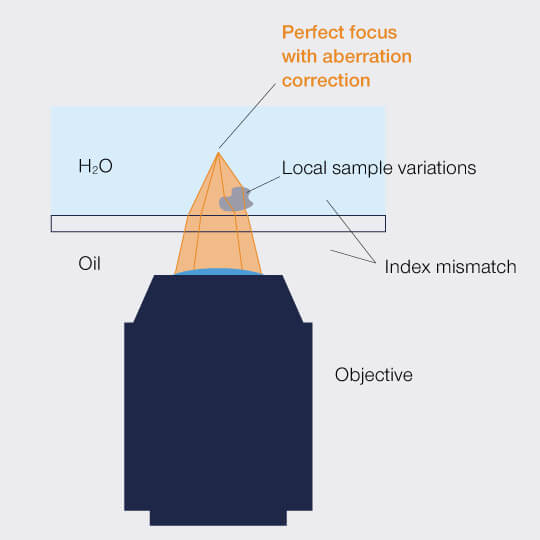

Certainly not! Scientists pondering the aberration problem for quite a while came up with a solution: It should be possible to compensate for aberrations by introducing a corrective in the beam path that has the opposite effect. Since aberrations are a function of the sample, immersion and embedding media, and wavelength, the operator must be able to adapt the correction for it to be useable in practice.

One option to this end is to use an objective lens containing movable groups of lenses that can be adjusted to correct for aberrations. However, these correction collar objectives suffer from a number of relevant limitations: As they work mechanically, their settings are poorly reproducible and some imprecision will always remain. Furthermore, they fail when confronted with irregular aberrations as introduced by e.g. sample inhomogeneities. They are also rather slow and even when motorized they cannot dynamically adapt their correction while focusing through the specimen. This means that you have to decide where in your sample you want to restore your signal: On top, somewhere in the middle, or at the bottom? The rest will always remain dark and murky. In consequence, correction collar objectives are poorly suited for 3D scans.

And then there is the issue that the objective best suited to your embedding medium might not be available with a correction collar.

Another problem is that correction collar objectives push the focus out of its original position as soon as their lenses are shifted to compensate for aberration, a phenomenon familiar from zoom objectives in photography.

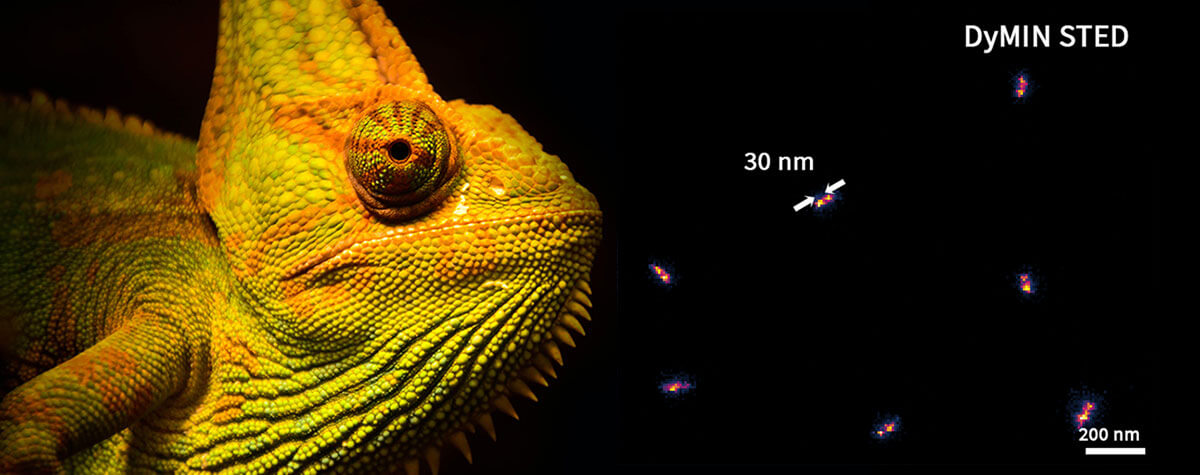

In summary, correction collar objectives can in principle compensate for aberrations, but this only works well for static images of sufficiently homogeneous samples and for a very limited depth range. Their shortcomings are even more evident when it comes to superresolution microscopy. When taking images with nanometer resolution, the coarse imprecision of a mechanical system becomes unacceptable.

Dynamic correction

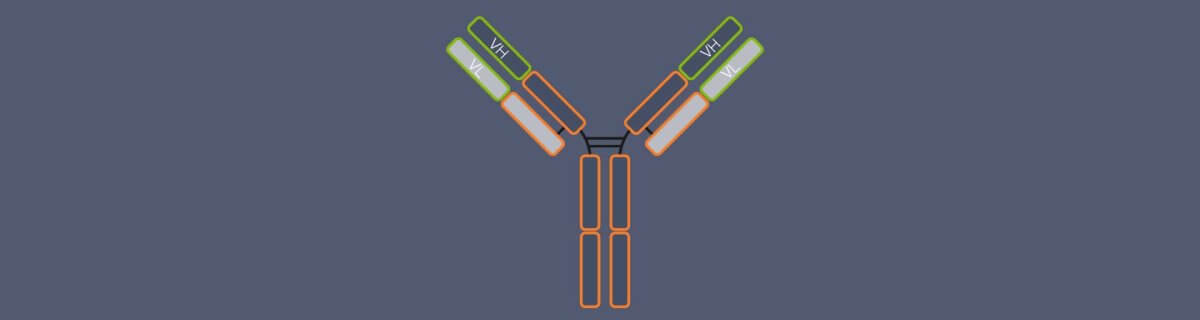

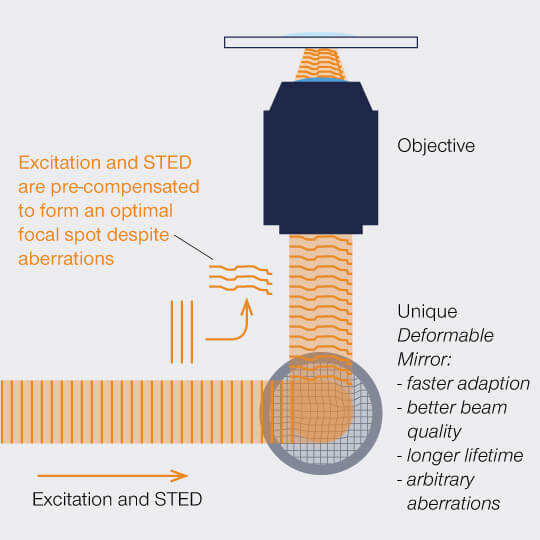

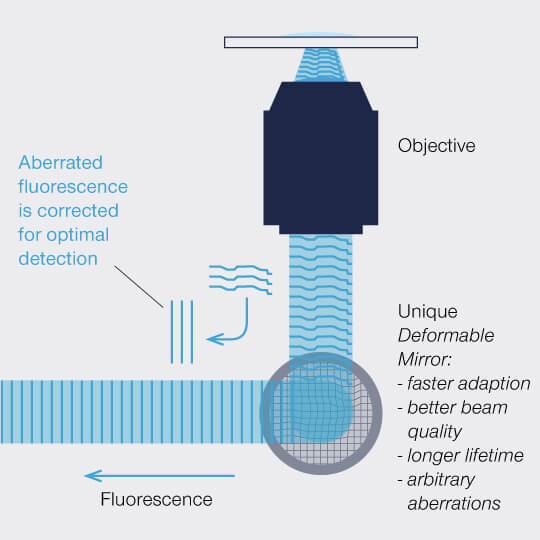

So let’s dismiss this solution and hand over the stage to adaptive optics: This strategy takes a different approach to put diverted rays back on track by applying a deformable mirror whose surface can be shaped as desired. 140 actuators pull on the membrane to make it resemble the distortions introduced by the sample, but in the opposite direction. In other words, the mirror’s surface is a negative of the wavefront error and can thus cancel aberrations.

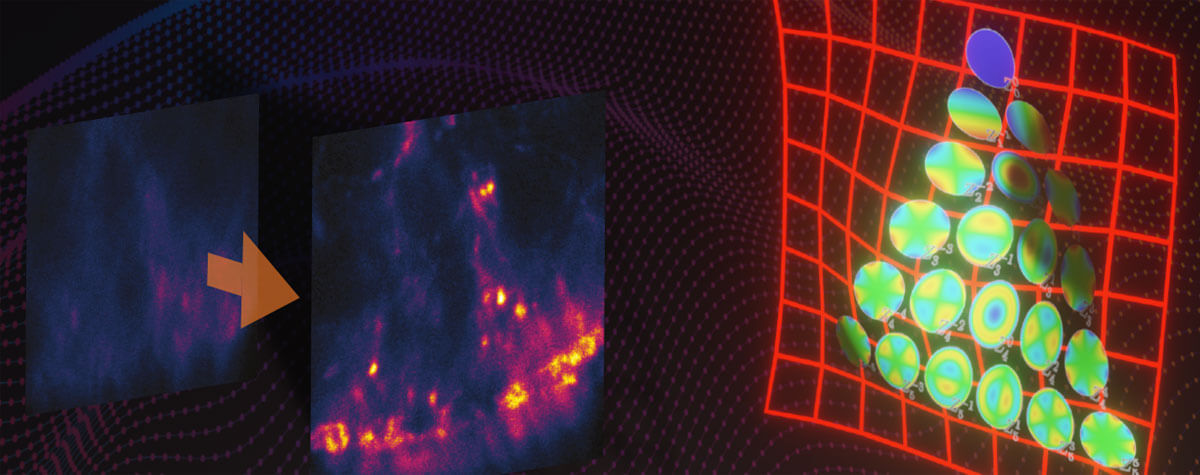

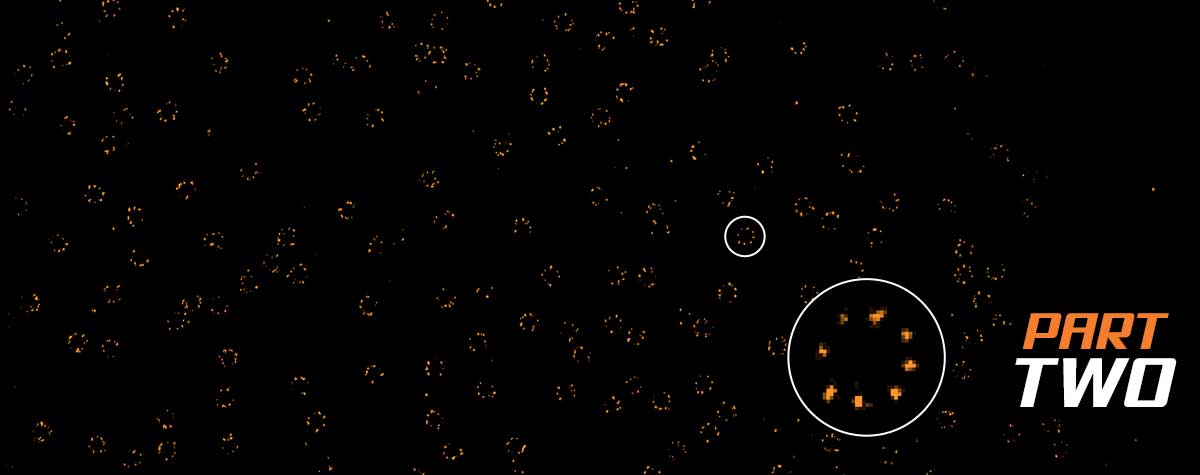

Figure 2: A deformable mirror can manipulate the wavefront of a) excitation light to pre-compensate and b) fluorescence to correct for aberrations.

The correction achieved withadeformable mirror is highly precise and can be adapted to different situations quickly, for example to varying focusing depths. As the actuators are controlled electronically, this happens within milliseconds so that the correction can dynamically follow the focus during z scans, guaranteeing perfect correction along the complete axis. And this is possible on the fly and without influencing the focus. Adaptive optics with a deformable mirror thus outperforms correction collar objectives in every relevant aspect and image acquisition runs completely autonomously for bright, high-resolution images from the top down deep into the sample.