PALM vs STORM …

PALM and STORM are often used as synonyms, and in fact they have a lot in common. But there are slight differences that can be important for your application. And then there are other superresolution techniques, too – like STED and MINFLUX.

… vs ???

How to achieve superresolution

At the end of the day, a lot of the distinction between photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) is historical. They were developed at around the same time and given two different names by their respective inventors. In practice, PALM and STORM are often used interchangeably or subsumed under terms like “blinking microscopy” or “single molecule localization microscopy” (SMLM). From a hardware perspective, there are zero differences anyway. Both techniques require a good microscope stand with strong widefield illumination, a high-end objective, and a fast, sensitive camera.

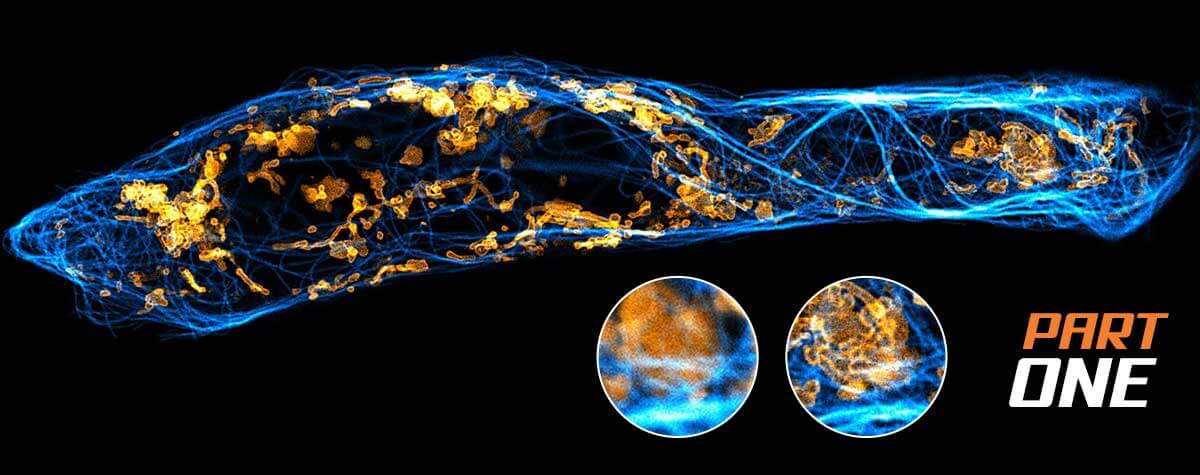

To find noticeable differences between PALM and STORM, we need to look at what they have in common first: both are types of superresolution fluorescence light microscopes. Other examples of such microscopes are stimulated emission depletion (STED) and MINFLUX, which offers even more performance.

In a “normal” fluorescence microscope, the resolution is limited to about 200 nanometers by diffraction. Diffraction blurs the image of individual dye molecules and because of this, molecules that are close together cannot be seen separately. The image becomes fuzzy and details beyond the diffraction limit cannot be detected.

Without exception, all available superresolution techniques circumvent this problem by manipulating individual dye molecules such, that they do not light up at the same time. This in turn makes it possible to image them separately, despite them being blurred by diffraction.

There are roughly two approaches for this manipulation. Well, in fact, three.

Different approaches

Historically, the first one was STED microscopy, where a donut-shaped second “off-switching” light beam ensures that all emitters are dark – except for a small ensemble in the center, in the dark hole of the donut, where there is no off-switching light. Effectively, this silences most of the molecules that would otherwise emit at the same time. Thus, resolution is increased, with the advantage that this method is physically very direct and does not require any mathematical processing. STED is a point scanning method and can upgrade existing laser scanning microscopes.

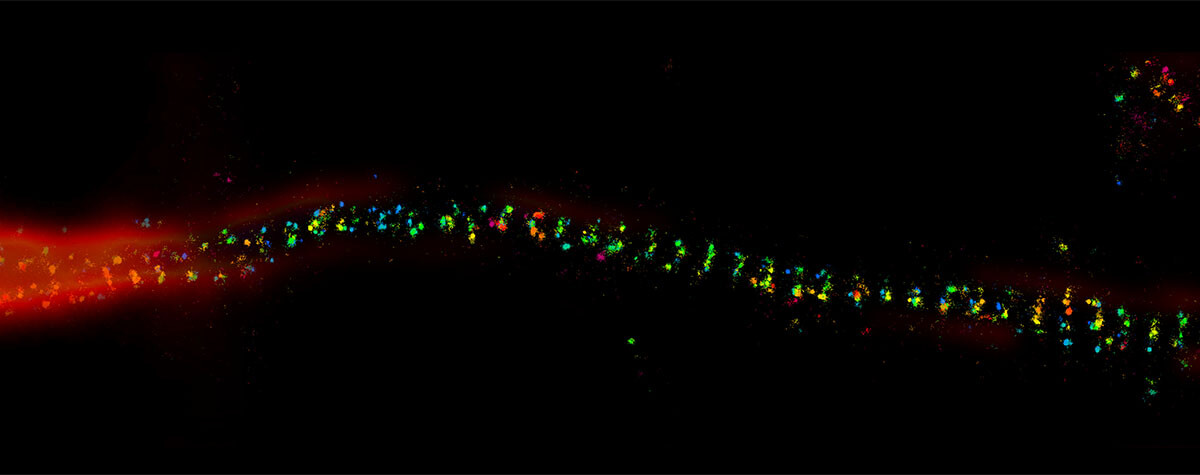

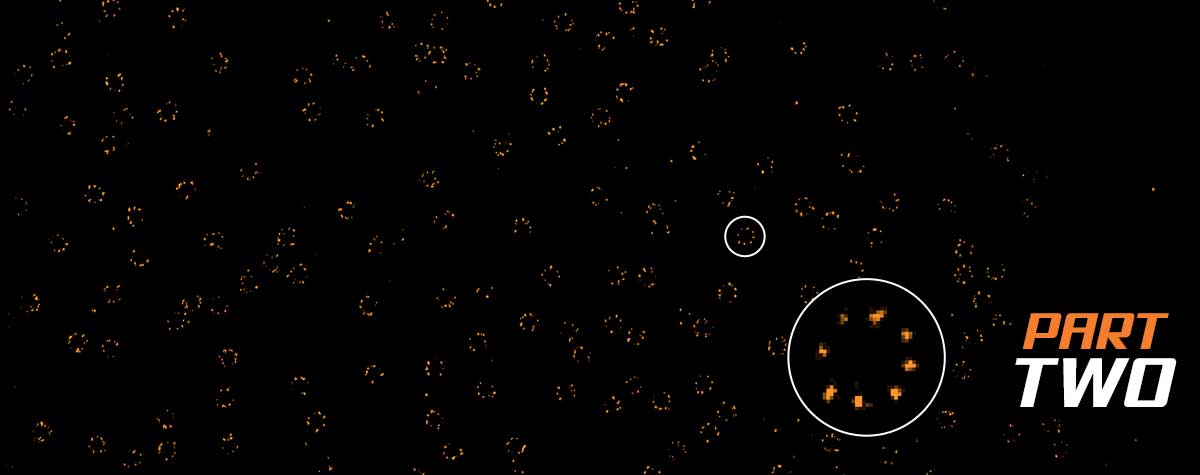

Second, there are those methods that randomly keep fluorescent molecules in a dark state most of the time. Then, they allow a few of them to light up briefly, so that within a radius of 200 nanometers only one emitter is bright at a time. Although its image is still blurred, its center of mass can be located very precisely and thus the position of the molecule is also clear. PALM and STORM belong to this group. They take many images of isolated molecules on a camera and use software algorithms to determine their positions offline. All positions plotted in one image then result in the final high-resolution picture.

Before we get to the third approach, what is the difference between PALM and STORM now? In short, it’s not a big one. In fact, it is solely the type of fluorescent molecule. STORM uses organic dyes (e.g. abberior FLUX, Alexa Fluor 647 or Cy5) that stochastically flicker under certain chemical conditions. They are attached to their target structure for example by means of labeled antibodies and require a dedicated buffer. For PALM, on the other hand, photoactivatable or -convertible fluorescent proteins are used (mCherry, mEOS, etc.). To this end, the cell is genetically modified so that when it produces its own proteins, it attaches a fluorophore by itself. This makes the staining of living cells relatively easy. For capturing an image, a random subset of non-overlapping fluorophores is then stochastically activated and imaged before they bleach, and the next subset is imaged.

A short overview

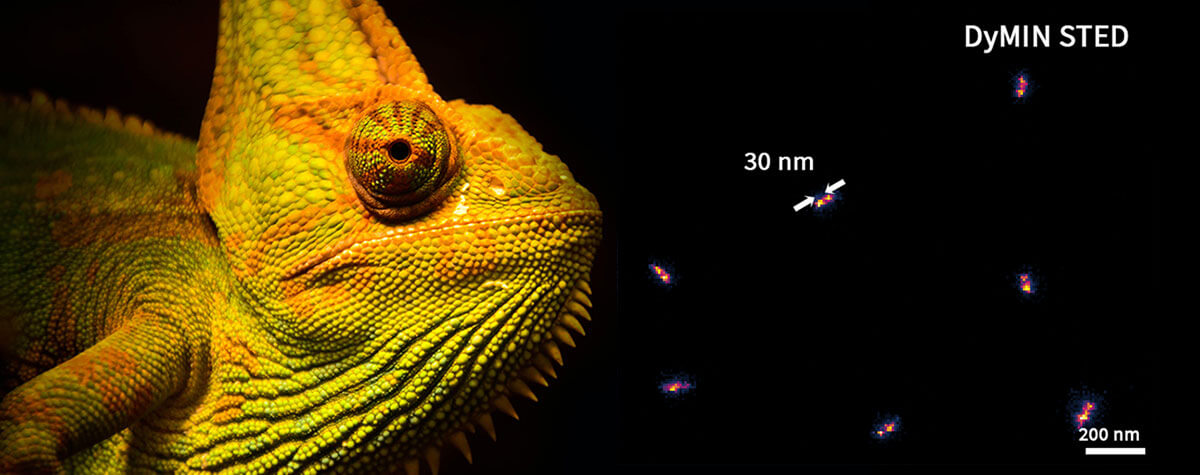

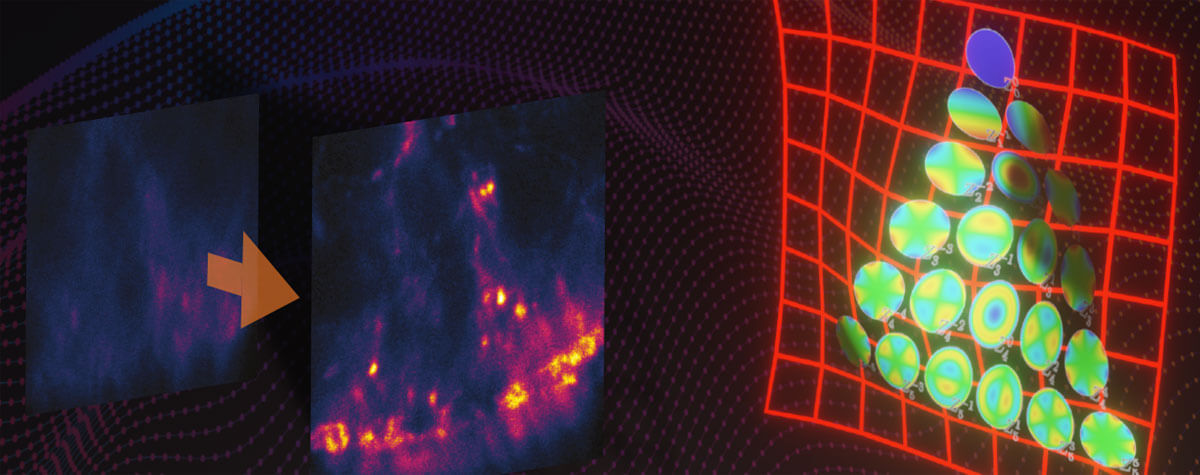

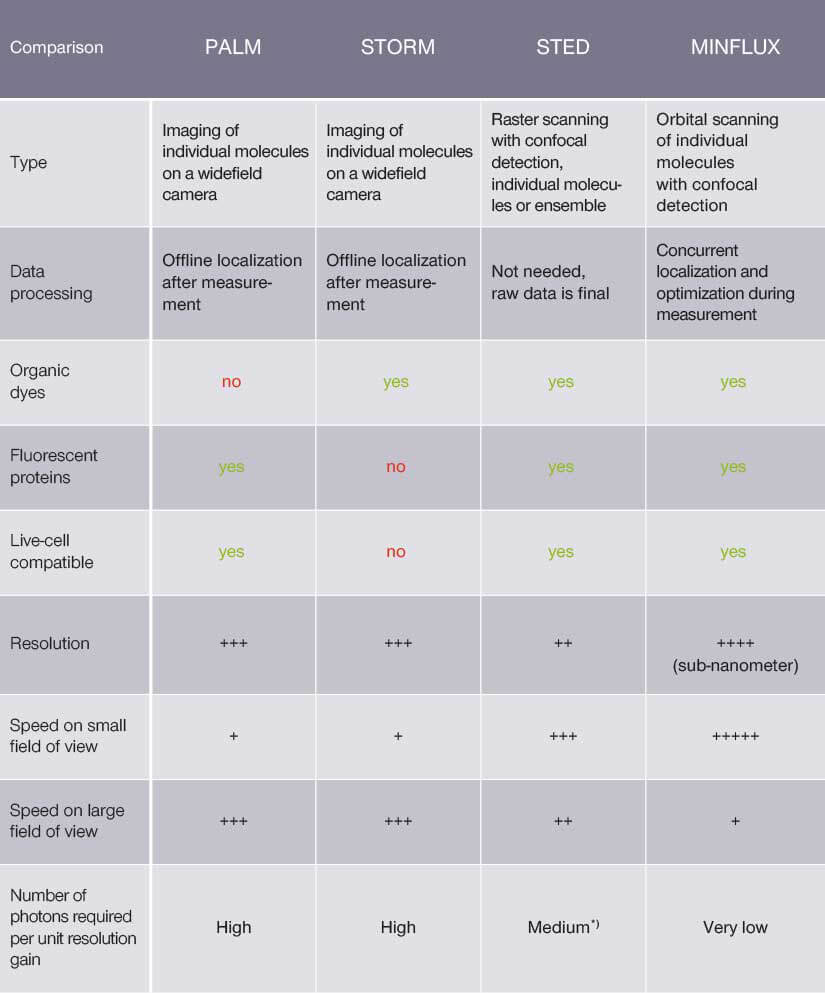

*with Adaptive Illumination

A comparison of PALM, STORM, STED and MINFLUX.

With both methods, the user must ensure that there are no two fluorophores in an emitting state within a diffraction limited region at the same time; otherwise, they would be counted as one molecule at a position exactly in between. For STORM, this means that the concentration of the buffer must be adjusted so that enough molecules are on, but not too many, to avoid the risk of overlap. With PALM, the user has to regulate the intensity of the activation laser for the same effect.

In general, there is obviously a certain effort involved to push the resolution beyond the diffraction limit. With PALM/STORM, most of the intricacy is in the sample preparation and the correct analysis of the raw camera images, for which the user is responsible. In contrast, STED requires more complex instrumentation, but the responsibility for success is more on the side of the instrument. The good thing is, commercial companies like abberior have nowadays taken care of this and using STED instruments is as straightforward as using a confocal microscope.

The third approach: MINFLUX

But why do we need a third option now? It becomes necessary when PALM/STORM or STED reach their limits. Although both can theoretically achieve unbounded resolution, in practice they do not. This is because the resolution depends on the number of photons, and no amount of photons can become arbitrarily large. The numbers may be high, but they are not unlimited and so is the resolution. But yet another technique, MINFLUX, gets around this by combining the advantages of blinking molecules with the advantages of using a donut-shaped light beam. MINFLUX is much more economical with photons than PALM/STORM and STED, and the savings can be invested in higher, even sub-nanometer resolution, and in much higher speeds. This is the reason why MINFLUX has a resolution even better than the size of a molecule and can measure their position several thousand times per second.

MINFLUX at a glance >